The Eleventh Judicial Circuit Criminal Mental Health Project (CMHP), located in Miami-Dade County, FL, was established in 2000 to divert individuals with serious mental illnesses (SMI; eg, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, andmajor depression) or co-occurring SMI and substance use disorders away from the criminal justice system and into comprehensive community-based treatment and support services. The program operates two primary components:prebooking jail diversion consisting of Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training for law enforcement officers and postbooking jail diversion serving individuals booked into the county jail and awaiting adjudication. In addition, the CMHP offers a variety of overlay services intended to: streamline screening and identification of program participants;develop evidence-based community reentry plans to ensure appropriate linkages to community-based treatment and support services; improve outcomes among individuals with histories of noncompliance with treatment; and expedite access to federal and state entitlement benefits. The CMHP provides an effective, cost-efficient solution to a community problem and works by eliminating gaps in services, and by forging productive and innovative relationships among all stakeholders who have an interest in the welfare and safety of one of our community’s most vulnerable populations.

Every day, in every community in the United States, law enforcement agencies, courts, and correctional institutions are witness to a parade of misery brought on by untreated or under-treated mental illnesses. According to the most recent prevalence estimates, roughly 16.9% of jail detainees (14.5% of men and 31.0% of women) experience serious mental illnesses (SMI).Considering that in 2018 law enforcement nationwide made an estimated 10.3 million arrests,2 this suggests that more than 1.7 million involved people with SMIs.

It is estimated that three-quarters of these individuals also experience co-occurring substance use disorders, which increases the likelihood of becoming involved in the justice system3 (National GAINS Center, 2005). On any given day, approximately 380 000 people with mental illnesses are incarcerated in jails and prisons across the United States.5 Considering that as of 2016 there were only about 20 000 beds in civil state psychiatric hospitals,6 this means that there are 19 times as many people with mental illnesses in correctional facilities as there are in all civil state treatment facilities combined.

Although these national statistics are alarming, the problem is even more acute in Miami-Dade County, FL. The county jail currently serves as the largest psychiatric institution in Florida and contains as many beds serving inmates with mental illnesses as all state civil and forensic mental health hospitals combined. On any given day, approximately 2400 of the 4200 individuals housed in the county jail (57%) are classified as having some mental health treatment need.7 Based on a total per diem cost of $265 per bed, the estimated cost to taxpayers is $636 000 per day, or more than $232 million per year.

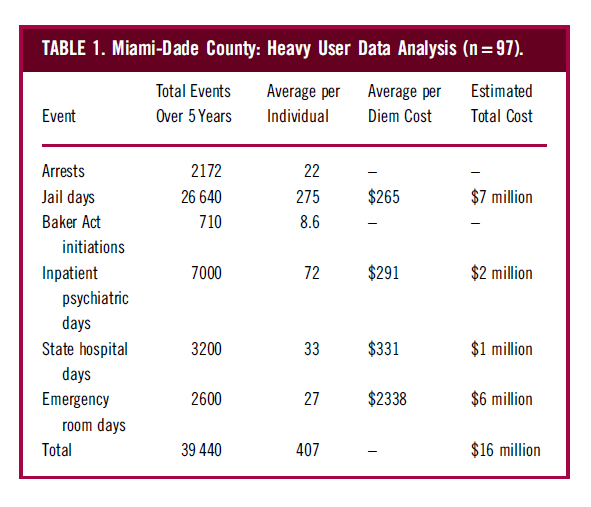

On average, people with mental illnesses remain incarcerated eight times longer than people without mental illnesses arrested for the exact same charge, at a cost seven times higher.8 With little treatment available, many individuals cycle through the system for the majority of their adult lives. To illustrate the inefficient and costly consequences of the current system, researchers from the Florida Mental Health Institute at the University of South Florida examined arrest, incarceration, acute care, and inpatient service utilization rates among 97 individuals with SMIs participating in jail diversion programs in Miami-Dade County, FL.

Individuals were selected for inclusion in the analysis based on their identification as frequent recidivists to the criminal justice system and acute care settings as defined by having been referred for diversion from jail to acute care crisis units on four or more occasions as the result of four or more discrete arrests. Total number of referrals for diversion services per individual ranged from 4 to 17, with an average of 7.1 referrals. Total number of lifetime bookings into the county jail ranged from 8 to 104, with an average of 36.6 bookings. As illustrated in Table 1, over a 5-year period, these individuals accounted for nearly 2200 arrests, 27 000 days in jail, and 13 000 days in crisis units, state hospitals, and emergency rooms, at a cost to taxpayers of roughly $16 million.

The Eleventh Judicial Circuit Criminal Mental Health Project (CMHP) was established 19years ago to divert misdemeanor offenders with SMI, or co-occurring SMI and substance use disorders, away from the criminal justice system into community-based treatment and support services. Since that time, the program has expanded to serve defendants that have been arrested for less serious felonies and other charges as determined appropriate.

The program operates two components: prebooking diversion consisting of Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training for law enforcement officers and postbooking diversion serving individuals booked into the jail and awaiting adjudication. All participants are provided with individualized transition planning including linkages to communitybased treatment and supports. Services available to program participants include supportive housing, supported employment, assertive community treatment, illness selfmanagement and recovery (wellness recovery action planning), trauma services, and integrated treatment for co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders.

Short-term benefits include reduced numbers of defendants with SMI in the county jail, as well as more efficient and effective access to housing, treatment, and wraparound services for individuals re-entering the community. This decreases the likelihood that individuals will re-offend and reappear in the criminal justice system, and increases the likelihood of successful mental health recovery. The long-term benefits include reduced demand for costly acute care services in jails, prisons, forensic mental health treatment facilities, emergency rooms, and other crisis settings; decreased crime and improved public safety; improved public health; decreased injuries to law enforcement officers, and people with mental illnesses; and decreased rates of chronic homelessness. Most importantly, the CHMP is helping to close the revolving door which results in the devastation of families and the community, the breakdown of the criminal justice system, wasteful government spending, and the shameful warehousing of some of our communities most vulnerable and neglected citizens.

Initial support for the development of the CMHP was provided in 2000 through a grant from the National GAINS Center,1 which enabled the court to convene a 2-day summit meeting of traditional and nontraditional stakeholders throughout the community. The purpose of the summit was to review the ways in which Miami-Dade County collectively responded to people with mental illnesses involved in the justice system. The GAINS Center provided technical assistance and helped the community map existing resources, identify gaps in services and service delivery, and develop a more integrated approach to coordinating care.

Stakeholders included judges and court staff, law enforcement agencies and first responders, attorneys, mental health and substance abuse treatment providers, state and local social service agencies, consumers of mental health and substance abuse treatment services, and family members. What was revealed was an embarrassingly dysfunctional system. Prior to the summit, it was readily apparent that people with mental illnesses were over-represented in the justice system.

What was not readily apparent, however, was the degree to which stakeholders were unwittingly contributing to and perpetuating the problem. Many participants were shocked to find that a single person with mental illness was accessing the services of TABLE 1. Miami-Dade County: Heavy User Data Analysis (n = 97). Event Total Events Over 5 Years Average per Individual Average per Diem Cost Estimated Total Cost Arrests 2172 22 – – Jail days 26 640 275 $265 $7 million Baker Act initiations 710 8.6 – – Inpatient psychiatric days 7000 72 $291 $2 million State hospital days 3200 33 $331 $1 million Emergency room days 2600 27 $2338 $6 million Total 39 440 407 – $16 million 1 The National GAINS Center is a federally funded organization concerned with the collection and dissemination of information about the effective services for people with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders in contact with the justice system.

GAINS is an acronym, which stands for gathering information, assessing what works, interpreting/integrating facts, networking, and stimulating change. More information may be found at: http://gainscenter.samhsa.gov/. 660 STEVE LEIFMAN AND TIM COFFEY https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920000127 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 50.113.85.24, on 29 Oct 2020 at 17:59:47, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at almost everybody in the room including law enforcement, emergency medical services, mental health crisis units, emergency rooms, hospitals, homeless shelters, jails, and the courts. Furthermore, this was occurring over and over as individuals revolved between a criminal justice system that was never intended to handle overwhelming numbers of people with serious mental illnesses and a community mental health system that was ill-equipped to provide the necessary services to those most in need.

A common theme among summit participants was the frustration of repeatedly serving the same individuals with seemingly little that could be done to break the cycles of crises, homelessness, recidivism, and despair. Part of the problem was that stakeholders were largely disconnected from one another and no mechanisms were in place to coordinate resources or services. Everyone was so busy doing their jobs that no one was looking at the bigger picture to see the ways in which individual roles come together to impact the welfare of the system, and the individual, as a whole. The police were policing, the lawyers were lawyering, and the judges were judging. Treatment providers knew little about what went on when their clients were arrested and, because of barriers to accessing information and laws that prohibit reimbursement for services provided to peoplewho are incarcerated, had little incentive to learn.

For individuals who had no resources to pay for services (eg, insurance and Medicaid), crisis units, hospitals, and the jail were often the only options to receive care. Ironically, while many individuals could not access themost basic prevention and treatment services in the community, they were being provided the costliest levels of crisis and emergency care over and over again. The degree of fragmentation in the community not only prevented the mental health and criminal justice systems from responding more effectively to people with mental illnesses, but also actually created increased opportunities for people to fall through the cracks.

The conclusion of the summit became apparent that people with untreated serious mental illnesses are among the most expensive population in the community not because of their diagnoses, but because of the way the health care and justice systems treat them. Using information generated from the summit meeting, program operations were initiated on a limited basis. Additional funding was secured from a local foundation to conduct a planning study of the mental health status and needs of individuals arrested and booked into the county jail, as well as the processes in place to link individuals to community-based services and supports.

Information from this planning study was used to develop a more formal program design and to secure a federal grant in 2003, which enabled the CMHP to significantly expand its staffing and operations. At the conclusion of the federal grant period, continuation of funding for all positions was assumed by the county. Because of the early success of the program and demonstrated outcomes, the CMHP was awarded another grant in 2007 by the State of Florida to further expand postbooking diversion operations to serve people charged with less serious felonies.

In 2010, another state grant was awarded, which was used to establish a specialized unit to expedite access to federal entitlement benefits. A 2016 grant supported the creation of jail in-reach team to streamline identification and assessment of program participants and support evidence-based re-entry planning. Finally, in 2018, the state funded a demonstration project to allow the CMHP to examine the impact of changes to state law allowing criminal court judges presiding over misdemeanor cases to leverage treatment compliance by ordering outpatient treatment under the state’s civil commitment laws. Since its inception, the CMHP has received ongoing support from the Florida Department of Children and Families.

In addition, since 2010, the CMHP has worked closely with ThrivingMind South Florida, which contracts with the state to administer non-Medicaid, mental health, and substance abuse treatment state funding for the uninsured and underinsured in Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties. Supplemented by additional federal, state and county grants and contracts as well as philanthropic support, ThrivingMindmanages a safety net systemof care for the treatment ofmental health and substance use disorders which is indispensable to the success of the CMHP. The CMHP’s success and effectiveness depend on the commitment, consensus, and ongoing effort of stakeholders throughout the community.To this end, the courts are in a unique position to bring together stakeholders who otherwise may not have opportunities to engage in such problem-solving collaborations.

In establishing the CMHP, a mental health committee was established within the courts. In addition, a local chapter of the statewide advocacy organization, Florida Partners in Crisis, was formed. Both of these bodies are chaired by the judiciary and provide a venue and opportunity for discussion of issues that cut across community lines. This has been particularly effective in resolving problems that arise from poor communication and cross-systems fragmentation. Staff for the CMHP are employed through a combination of the Administrative Office of the Courts, Thriving Mind South Florida, and Community Health of South Florida, a local treatment provider, and work closely with all stakeholders in the community. Funding for staff positions comes fromcounty, state, and federal sources and consists of a mix of general revenue and grant funding.

The CMHP has embraced and promoted the CIT training model developed in Memphis, Tennessee in the late 1980s.Known as the Memphis Model, the purpose of CIT training is to set a standard of excellence for law enforcement officers with respect to the treatment of individuals with mental illnesses. CIT officers perform regular duty assignment as patrol officers, but are also trained to respond to calls involving mental health crises.

Officers receive 40 hours of specialized training in psychiatric diagnoses, suicide intervention, substance abuse issues, behavioral de-escalation techniques, the role of the family in the care of a person with mental illness, mental health and substance abuse laws, and local resources for those in crisis. The training is designed to educate and prepare officers to recognize the signs and symptoms of mental illnesses, and to respond more effectively and appropriately to individuals in crisis.

Because police officers are often the first responders to mental health emergencies, it is essential that they know how mental illnesses can impact the behaviors and perceptions of individuals. CIT officers are skilled at de-escalating crises,while bringing an element of understanding and compassion to these difficult situations. When appropriate, individuals are assisted in accessing treatment in lieu of being arrested and taken to jail. Because CIT programs are in operation in jurisdictions and municipalities countywide, and officers are called on to respond to a variety of situations ranging from relatively minor incidents to urgent crises, there is no single point of entry and no standard intervention provided.

Rather, officers are trained to quickly assess situations and assist individuals in accessing a full array of crisis and noncrisis services and resources across the community. These include providing transportation to hospitals and crisis stabilization units in emergency situations, accessing the services of a mobile crisis team consisting of mental health professionals providing onsite assessment and referral services in the community, and providing informational resources to assist individuals in locating and accessing health and social services throughout the county.The prebooking diversion program has demonstrated tremendous results. To date, theCMHP has provided CIT training to more than 7000 law enforcement officers from all 36 local municipalities in Miami-Dade County, as well as Miami-Dade Public Schools and the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Countywide, CIT officers are estimated to respond to nearly 20 000 mental health crisis calls per year.

As indicated in Table 2, since 2010, CIT officers from the Miami-Dade Police Department and City of Miami Police Department have responded to 91 472 mental health crisis calls resulting in 17 516 diversions from jail, 55 013 individuals assisted in accessing community-based treatment, and just 152 arrests. Since 2008, the number of annual jail bookings has decreased from roughly 118 000 to 53 000 last year (see Figure 1). The average daily population in the county jail system has dropped from 7200 to 4200 inmates today (see Figure 2), and the county has closed one entire jail facility at a costsavings to taxpayers of $12 million per year.

TheCMHPwas originally established to divert nonviolent misdemeanant defendants with SMI and possible co-occurring substance use disorders, from the criminal justice system into community-based treatment and support services. Since that time, the program has been expanded to serve defendants that have been arrested for less serious felonies and other charges as determined appropriate. All defendants booked into the jail are screened for signs and symptoms of mental illnesses by correctional officers using an evidence-based screening tool. Additionally, defendants undergo medical screening by health care staff at the jail, which includes additional assessment of psychiatric functioning. Those who are identified as being in possible psychiatric distress are referred to corrections health services’ psychiatric staff for more thorough evaluation. In order to determine the appropriate level of treatment, support services and community supervision, the CMHP screens each program participant with regard to mental health and substance use treatment needs, as well as criminogenic risks factors. A two-page summary is developed that is used to develop an individualized transition plan aimed at reducing criminal justice recidivism and improved psychiatric outcomes, recovery, and community integration.

The evidence-based screening tools include the Texas Christian University Drug Screen V11 and the Ohio Risk Assessment: Community Supervision Tool.12 Upon stabilization, legal charges may be dismissed or modified in accordance with treatment engagement. Individuals who voluntarily agree to services are assisted with linkages to a comprehensive array of community-based treatment, support, and housing services that are essential for successful community re-entry and recovery outcomes. The CMHP utilizes the APIC Model to provide transition planning for all programparticipants.13 This is a nationally recognized best practicemodel that provides a set of critical elements that improve outcomes for people with mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders that are released from jails. CMHP staff assess, plan, identify, and coordinate transition plans that are individualized for each program participant. The goal is to support community living, reduce maladaptive behaviors, and decrease the chances that individuals will re-offend and reappear in the criminal justice system.

Individuals charged with misdemeanors who meet involuntary examination criteria are transferred from the jail to a community-based crisis stabilization unit as soon as possible. Upon stabilization, legal charges may be dismissed or modified in accordance with treatment engagement. Individuals who agree to services are assisted with linkages to a comprehensive array of community-based treatment, support, and housing services that are essential for successful community re-entry and recovery outcomes.

Program participants are monitored by CMHP for up to 1 year following community re-entry to ensure ongoing linkage to necessary supports and services. The vast majority of participants (75%-80%) in the misdemeanor diversion program is homeless at the time of arrest and tends to be among the most severely psychiatrically impaired individuals served by the CMHP. Felony jail diversion program Participants in the felony jail diversion program are referred to the CMHP through a number of sources including the Public Defender’s Office, the State Attorney’s Office, private attorneys, judges, corrections health services, and family members. All participants must meet diagnostic and legal criteria.2 At the time a person is accepted into the felony jail diversion program, the state attorney’s office informs the court of the plea the defendant will be offered contingent upon successful program completion. Similar to themisdemeanor program, legal charges may be dismissed or modified based on treatment engagement.

All program participants are assisted in accessing community-based services and supports, and their progress ismonitored and reported back to the court by CMHP staff. Jail diversion program outcomes Recidivism rates among participants in the misdemeanor jail diversion program have decreased roughly from 75% to 20% annually. Individuals participating in the felony jail diversion program demonstrate reductions in jail bookings and jail days of more than 75%. Since 2008, total jail bookings and days spent in the county jail among felony jail diversion program participants decreased by 59% and 57%, respectively, resulting in a difference of approximately 31 000 fewer days in jail (nearly 84 years of jail bed days). Recovery peer specialists Embedded in both the misdemeanor and felony jail diversion programs, recovery peer specialists are individuals diagnosed with mental illnesses who work as members of the jail diversion team. Due to their life experience, they are uniquely qualified to perform the functions of the position. The primary function of the <*Recovery peer specialists is to assist jail diversion program participants with community re-entry and engagement in continuing treatment and services.

This is accomplished by working with participants, caregivers, family members, and other sources of support to minimize barriers to treatment engagement, and to model and facilitate the development of adaptive coping skills and behaviors. Recovery peer specialists also serve as consultants and faculty to the CMHP’s CIT training program. Access to entitlement benefits Stakeholders in the criminal justice and behavioral health communities consistently identify lack of access to public entitlement benefits such as supplemental security income (SSI), social security disability insurance (SSDI), and Medicaid as among the most significant and persistent barriers to successful community re-integration and recovery for individualswho experience seriousmental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders.

The majority of individuals served by the CMHP are not receiving any entitlement benefits at the time of program entry. As a result,many do not have the necessary resources to access adequate housing, treatment, or support services in the community. In order to address this barrier and maximize limited resources, the CMHP developed an innovative plan to improve the ability to transition individuals from the criminal justice system to the community. Toward this goal, all participants in the program who are eligible to apply for Social Security benefits are provided with assistance utilizing a best practice model referred to as SSI/SSDI, Outreach, Access, and Recovery (SOAR).14 This is an approach that was developed as a federal technical assistance initiative to expedite access to social security entitlement benefits for individuals with mental illnesses who are homeless.

Access to entitlement benefits is an essential element in successful recovery and community reintegration for many justice system involved individuals with serious mental illnesses. The immediate gains of obtaining SSI and/or SSDI for these people are clear: it provides a steady income and health care coverage which enables individuals to access basic needs including housing, food, medical care, and psychiatric treatment. This significantly reduces recidivism to the criminal justice system, prevents homelessness, and is an essential element in the process of recovery. The CMHP has developed a strong collaborative relationship with the Social Security Administration in order to expedite and ensure approvals for entitlement benefits in the shortest time frame possible.

All CMHP participants are screened for eligibility for federal entitlement benefits, with staff initiating applications as early as possible utilizing the SOAR model. Current program data demonstrate that 78% of the individuals are approved on the initial application. By contrast, the national average across all disability groups for approval on initial application is 27%. In addition, the average time to approval for CMHP participants is approximately 40 days. This is a remarkable achievement compared to the ordinary approval process which typically takes between 9 and 12 months.

Since August 2009, the CMHP has overseen the implementation of the Miami-Dade Forensic Alternative Center (MD-FAC) to divert individuals with mental illnesses committed to the Florida Department of Children and Families from placement in state forensic hospitals to placement in community-based treatment and forensic services. Participants include individuals charged with second and third degree felonies that do not have significant histories of violent felony offenses and are not likely to face incarceration if convicted of their alleged offenses. Participants are adjudicated incompetent to proceed to trial or not guilty by reason of insanity. The community-based treatment provider operating services for the project is responsible for providing a full array of residential treatment and community re-entry services including crisis stabilization, competency restoration, development of community living skills, assistance with community re-entry, and community monitoring to ensure ongoing treatment following discharge.

The treatment provider also assists individuals in accessing entitlement benefits and other means of economic self-sufficiency to ensure ongoing and timely access to services and supports after re-entering the community. Unlike individuals admitted to state hospitals, individuals served by MD-FAC are not returned to jail upon restoration of competency, thereby decreasing burdens on the jail and eliminating the possibility that a person may decompensate while in jail and require readmission to a state hospital. To date, the project has demonstrated more cost effective delivery of forensic mental health services, reduced burdens on the county jail in terms of housing and transporting defendants with forensic mental health needs, and more effective community re-entry and monitoring of individuals who, historically, have been at high risk for recidivism to the justice system and other acute care settings. Individuals admitted to the MD-FAC program are identified as ready for discharge from forensic commitment an average of 52 days (35%) sooner than individuals who complete competency restoration services in forensic treatment facilities, and spend an average of 31 fewer days (18%) under forensic commitment. The average cost to provide services in the MD-FAC program is roughly 32% less expensive than services provided in state forensic treatment facilities.

Since 2006, the CMHP has been working with stakeholders from Miami-Dade County, the State of Florida, and the community on a capital improvement project to develop a first of its kind mental health diversion and treatment facility which will expand the capacity to divert individuals fromthe county jail into a seamless continuum of comprehensive community-based treatment programs that leverage local, state, and federal resources. The purpose of theMiami Center for Mental Health and Recovery is to create a comprehensive and coordinated system of care for individuals with serious mental illnesses who are frequent and costly recidivists to the criminal justice system, homeless continuum of care, and acute care medical and mental health treatment systems.

The building—which encompasses approximately 181 000 square feet of space and capacity for 208 beds—will include a central receiving center, an integrated crisis stabilization unit and addiction receiving facility, various levels of residential treatment, day treatment and day activity programs, outpatient behavioral health and primary care treatment services, vocational rehabilitation and supportive employment services, and classroom/educational spaces. The facility will also include a courtroomand space for social service agencies, such as housing providers, legal services, and immigration services that will address the comprehensive needs of individuals served. Capital funding for the project is provided through the county’s general obligation bond program, with additional support provided by the Jackson Health System— Public Health Trust.

To expedite completion of the facility and contain costs, Miami-Dade County, with the support of the state, transferred of the project to Thriving Mind South Florida for the purposes of providing oversight of the construction phase and eventual operations. By housing a comprehensive array of services and supports in one location, and providing re-entry assistance upon discharge to the community, it is anticipated that many of the barriers and obstacles to navigating traditional community mental health and social services will be eliminated. The services planned for the facility will address critical treatment needs that have gone unmet in the past and reduce the likelihood of recidivism to the justice system, crisis settings, and homelessness in the future. Operation at the facility will begin in early 2021.

The CMHP has demonstrated substantial, cost-effective gains in the effort to reverse the criminalization of people with mental illnesses. The idea was not to create newtreatment services which may duplicate existing services in the community, but rather to create more efficient and effective linkages to these services. The Project works by eliminating gaps in services and by forging productive and innovative relationships among all stakeholders who have an interest in the welfare and safety of one of our community’s most vulnerable populations.

The CMHP offers the promise of hope and recovery for individuals with SMI that have often been misunderstood and discriminated against. Once engaged in treatment and community support services, individuals have the opportunity to achieve successful recovery, community integration, and reduce their recidivism to jail. The CMHP provides an effective and cost-efficient solution to a community problem. Program results demonstrate that individualized transition planning to access necessary community-based treatment and services upon release fromjail will ensure successful community re-entry and recovery for individuals with mental illnesses, and possible co-occurring substance use disorders that are involved in the criminal justice system.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.